NIKKOR The Thousand and One Nights No.96

The first fast medium-telephoto lens for the Nikon F

The Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8

We looked at the Nikon Mini compact camera with Tale 94, but I would like to return to interchangeable lenses, particularly a medium telephoto lens, with this Tale. The lens I would like to cover is the Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8, which was released five years after the Nikon F.

By Kouichi Ohshita

From the rangefinder era to the SLR era

Nikon has been familiar with 85mm lenses since the rangefinder era. The first was the Nikkor-P·C 8.5cm F2 released in April of 1949 and covered in Tale 36. As you know, this legendary lens established the Nikkor name around the world. Four years later, the Nikkor-S·C 8.5cm F1.5, introduced with Tale 19, was released in February of 1953. Considering the fact that the Nikon S was released around December of 1950 and the Nikon S2 in 1954, it's clear the Nikon lens lineup expanded with faster apertures before camera support for them did. 85mm lenses have been synonymous with fast medium-telephoto lenses since the days of rangefinder cameras.

Fast forward to 1959 when the Nikon F SLR was released. The initial lens lineup available by the end of 1959 included two medium-telephoto lenses, the Nikkor-P Auto 105mm F2.5 and the Nikkor-Q Auto 135mm F3.5, but not an 85mm lens. As Sato explained in Tales 5 and 45, 105mm and 135mm lens optics could reused when lenses were updated for use with SLR cameras, but the shorter focal length of the 85mm meant the lens had a short back focus that made a new design necessary. Further, in the early stages of Nikon F development, the focus was on wide-angle lenses, which required new designs, and telephoto lenses that would demonstrate the appeal of SLR cameras. This may have been another factor in the delay in releasing an 85mm lens.

The long-awaited Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8 was finally released five years later in August of 1964. It was the first fast medium-telephoto lens for the Nikon F.

The Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8

The Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8 was designed by Saburo Murakami, who plays a recurring role in The Thousand and One Nights. Murakami was involved in the optical design of numerous interchangeable lenses for rangefinder cameras, as well as early interchangeable lenses for the Nikon F. He was very well respected and contributed greatly to early Nikon interchangeable lenses. In Tale 40 I wrote that the Nikkor-S Auto 5.8cm F1.4 was probably the last interchangeable lens designed by Murakami, but in fact, the Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8 was the last lens with which he was involved. I would very much like to set the record straight on that matter.

Design of this lens likely began around 1961. At the time, Murakami served as number two of the Design Department (later the Camera Design Department), and likely worked on designing the lens while performing his managerial duties. The design was mostly complete and a report written in May of 1962. A prototype of the lens was produced that year, but a tendency to produce flare discovered with testing meant improvements were needed. Coma was improved for mass production without changing the basic design by modifying the curvature radii of the front element and rear lens group. The Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8 was finally released in August of 1964.

Lens construction

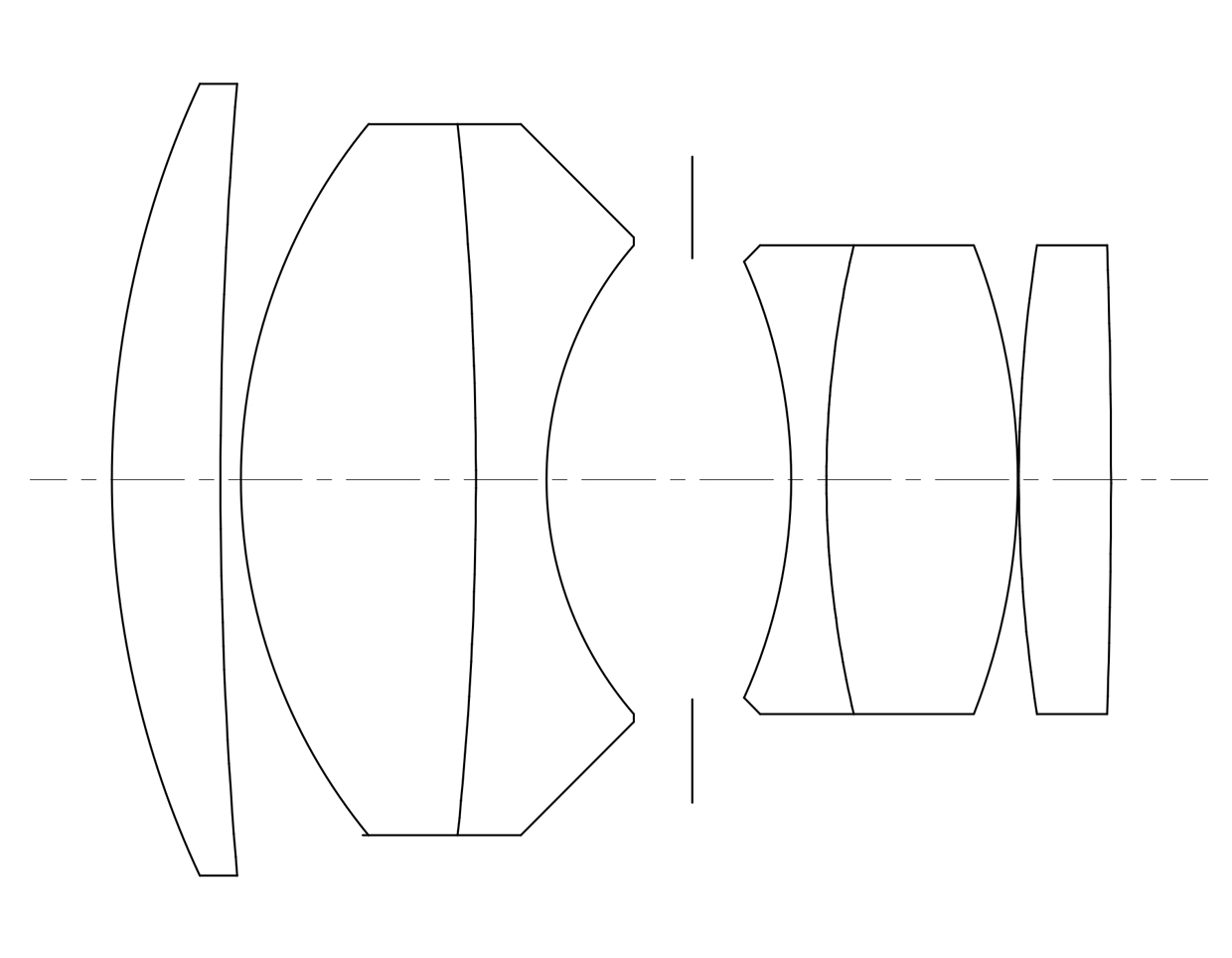

Fig. 1 is a cross section of the Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8 lens.

This lens has a conventional Gauss design with a convex first element, a convex second and concave third element cemented together to form a meniscus shaped doublet, the aperture, a concave fourth and convex fifth element that also form a doublet with an overall meniscus shape, and a convex sixth element. As mentioned in previous The Thousand and One Nights, the true value of a Gauss design is revealed when a high-refractive-index, low-dispersion glass such as lanthanum glass is used for the convex elements. The newly developed lanthanum glass was also used for the first and sixth elements, resulting in a lens with little spherical aberration and coma, and a very uniform image plane. However, lanthanum glass at that time had a lower refractive index than does today's lanthanum glass, it seems that some compromises had to be made in terms of performance. One such compromise was the residual astigmatism. The refractive index of each convex element was probably a little too low to align the meridional and sagittal image planes and flatten the overall image field. Therefore, the meridional image plane is left slightly positive and the sagittal image plane slightly negative, so that the average image plane is flattened and image uniformity is maintained. Another compromise is the remaining higher-order spherical aberration and coma. The curvature of spherical aberration with the original prototype was significant and then over-corrected. This aberration balance was intended to dramatically increase resolution and contrast when the aperture was stopped down, but test results showed a great deal of flare at maximum aperture. Therefore, the design was revised with spherical aberration shifted to a negative value and coma corrected accordingly. However, this did not reduce the higher-order aberration that causes flare, so there may be some situations that result in some flare when the aperture is wide open.

I've noted the drawbacks of this lens, but there is no doubt it was a high-performance lens during its time. Despite being a fast lens, it exhibits relatively little peripheral illumination falloff that is only an issue if you're looking for consistent rendering, as with astrophotography. In addition, the symmetrical Gauss design produces very little distortion or lateral chromatic aberration, allowing users to expect sharp and clear rendering, especially when the aperture is stopped down. High-order spherical aberration and a slight astigmatism do remain, however, which suggests that bokeh at maximum aperture may be distorted or harsh.

Lens rendering

As always, let's take a look at the rendering characteristics of this lens with actual images. The sample images for this Tale were captured using the full-frame Z 6 mirrorless camera with the FTZ mount adapter. I used an Ai-modified Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8 with multi-coating to capture these images. When a manual focus lens is used with the FTZ, shooting is performed with actual aperture metering, but the focal length and maximum aperture must be registered with the camera. It is important to register the focal length for effective use of on-board vibration reduction.

With a focal length of 85mm and a maximum aperture of f/1.8, the Nikkor-H Auto 85mm f/1.8 is the fastest lens with a 52mm filter attachment size. Despite this, however, the lens is tightly packed with lens elements, making it heavier than it looks with a weight of 420 g. In addition, the focus ring increases the maximum diameter of the lens to 72 mm for a stark contrast to the lightweight Nikon Lens Series E 100mm F2.8, another compact medium-telephoto lens introduced in Tale 80.

The following samples were captured in RAW format and processed with lateral chromatic aberration correction and vignette control disabled. Please note, however, that multiple images were combined and flattened after initial processing for Sample 3, so the amount of peripheral illumination is not accurately represented.

Z6 + FTZ w/ Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8

At maximum aperture, shutter speed of 1/2000 s, ISO 100; processed with NX Studio

Z6 + FTZ w/ Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8

At aperture setting of f/4, shutter speed of 1/640 s, ISO 100; processed with NX Studio

Samples 1 and 2 are distant shots of urban buildings. Sample 1 was captured at maximum aperture and Sample 2 with the aperture stopped down to f/4. Even at maximum aperture, Sample 1 is sharp and exhibits relatively high contrast from the center through approximately 50% of the frame. However, when compared with Sample 2, you will notice some flare and pale reddish-purple color bleed. Looking more closely at the edges of the frame, we see that Sample 1 exhibits more flare and that resolution drops for softer rendering. This is particularly noticeable with the TV antenna near the upper right corner of the frame. When the aperture is stopped down to f/4 as in Sample 2, there is no noticeable increase in peripheral flare or drop in resolution. Rendering is fairly uniform throughout the frame, with no visible color bleed at the edges. This demonstrates a very small amount of lateral chromatic aberration.

What's more, no distortion is evident in the samples above, despite the scene being composed entirely of straight lines. Distortion measures approximately +0.5% at infinity and less than 0.1% at a shooting distance of 1 m, making this a perfect lens for photographing linear subjects.

Z6 + FTZ w/ Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8

At maximum aperture, shutter speed of 6s (x 16 shots), ISO 1600; processed with NX Studio Combined 16 shots, flattened, then applied high-contrast processing with NX Studio

Z6 + FTZ w/ Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8

At aperture setting of f/8, shutter speed of 1/500 s, ISO 100; processed with NX Studio

Sample 3 is a photo of the Orion constellation captured at maximum aperture. Framing of the three second-magnitude stars at the center of the image, the first-magnitude stars Betelgeuse and Rigel at upper left and lower right, Bellatrix at upper right, and the second-magnitude star Saiph at lower left creates a beautiful and balanced composition. M42, the Orion Nebula, and M43 are located below the three stars, and just above Alnitak, the leftmost of the three stars, is NGC 2024, called the Flame Nebula, and just below it is IC 434 highlighting the Horsehead Nebula. In addition, a variety of nebulae, including M78 between Alnitak and Betelgeuse, add color to the image. This image was created by merging 16 six-second exposures and to reduce high-sensitivity noise, then flattening the image for an even background and applying high-contrast processing specific to astrophotography. This enhances faint flare and chromatic aberration, making them more noticeable.

Blue to reddish-purple flare is visible around the three brighter stars at the center of the frame. The brighter the star, the larger it appears in the image. This is the result of residual high-order spherical aberration and axial chromatic aberration that are the real cause of the flare visible at the center of the frame in Sample 1. If we look at the four first- and second-magnitude stars at the edges of the frame, we see that the reddish-purple flare has been distorted, fanning out toward the center of the frame. This is the result of residual coma. When coma extends toward the center of the frame, as in this sample image, it is called inward coma. The characteristics of coma change in accordance with the shooting distance, appearing slightly inward at infinity and outward at short distances. In addition, you can see that fainter stars at the edges of the frame are diamond-shaped rather than round points or circles. This is caused by astigmatism at the peripheries. The stars are distorted because focus cannot be acquired simultaneously in both the meridional and sagittal focal planes. The flare and loss of resolution at the edges of Sample 1 are also caused by this coma and astigmatism. The effects of astigmatism become less noticeable when the aperture is stopped down, and are almost completely eliminated at apertures between f/4 and f/5.6.

Sample 4 is a picture of an out-of-season plane tree shot with the aperture stopped down to f/8. As noted above, stopping down the lens to f/5.6 produces a uniform image across the entire frame, but I stopped the aperture down to f/8 to include the whole tree, from top to bottom, in the depth of field. This results in a very sharp and somewhat harsh image.

Z6 + FTZ w/ Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8

At maximum aperture, shutter speed of 1/1000 s, ISO 100; processed with NX Studio

Z6 + FTZ w/ Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8

At aperture setting of f/2.8, shutter speed of 1/320 s, ISO 100; processed with NX Studio

Sample 5, a photo of the berries on a Kurogane holly, was captured at maximum aperture from a short distance. Even at maximum aperture, the image exhibits high contrast. However, if you look closely at the leaves and berries at the edges of the frame, you will notice they appear to be slightly smeared in concentric circles. This is caused by the astigmatism indicated with Sample 3, and is one of the few flaws this lens exhibits.

You may also notice the background bokeh has been distorted into rugby ball shapes at frame peripheries, and that the edges of the bokeh are sharp. This may be somewhat distracting with a high-contrast background as in this photo.

Sample 6 is a picture of the same tree with the aperture stopped down to f/2.8. As you can see, stopping down the aperture a little softens the background bokeh, but because the aperture on this lens has a sharp hexagonal shape, the angular shape of the bokeh may still be distracting to some.

Z6 + FTZ w/ Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8

At maximum aperture, shutter speed of 1/2000 s, ISO 100; processed with NX Studio

Z6 + FTZ w/ Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8

At maximum aperture, shutter speed of 1/400 s, ISO 100; processed with NX Studio

Sample 7 is a photo of Taiwan cherry blossoms captured at maximum aperture. I shot this image at maximum aperture to omit as much of the background as possible, but at f/1.8, the depth of field is shallow and most of the flowers are out-of-focus. If you look closely at the flowers at the edges of the frame, you will see the blurred flowers are distorted by astigmatism, just as with Sample 5.

In Tale 30, I mentioned the fact that the extent of background bokeh depends on the effective diameter of the lens, and refers to a background located at infinity, sufficiently far from the subject. Meanwhile, the f-stop, which indicates the speed (brightness) of a lens, can be considered an indicator of how much of the area in front of and behind the subject will appear in-focus (i.e., depth of field). In other words, if the size of the focus subject relative to the frame is the same between an 85mm f/1.8 lens and a 135mm f/2.8 lens, which have roughly the same effective diameter, background bokeh will be similar, but the depth of field will be greater with the 135mm lens. This shallow depth of field is what makes the large-diameter 85mm lens so appealing, but also what makes it difficult to master.

Sample 8 is a picture of plum blossoms captured at the minimum focus distance and maximum aperture. The depth of field is even more narrow than in Sample 7, with the flowers at the tip of the branch below the center of the frame and the flowers at the center of the frame just barely in-focus. Even the flowers that are in-focus appear soft and slightly flared. This is the result of spherical aberration, which varies with shooting distance. There is a rather large amount of negative spherical aberration at the minimum focus distance that results in an overall soft, veiled appearance. The aperture must be stopped down from f/2.8 to f/4 to prevent this. This variation in spherical aberration at short distances is a fundamental characteristic of entire-lens extension focusing. The Ai Nikkor 85mm F1.4S introduced in Tale 89, which has an even faster (larger) f/1.4 aperture, is equipped with a close-range correction system that corrects this variation in spherical aberration. This is probably why the minimum focus distance for this lens is one meter.

Release and beyond

As I said before, this lens was released in August of 1964, but Murakami had retired the year before and entrusted mass production to a junior colleague. This was Murakami's last lens. He must have been very pleased when it was released. Ten years later, in June of 1974, multi-coating was added to the lens, and it was re-released as the Nikkor-H·C Auto 85mm F1.8. In June of 1975, its exterior was redesigned and it was once again released as the New Nikkor 85mm F1.8, making it a very popular lens for more than a decade.

However, with the release of Ai-compatible cameras in 1977, a fully redesigned optical system was adopted for Nikon's 85mm lens, which was released as the Ai Nikkor 85mm F2, and the Nikkor-H Auto 85mm F1.8 quietly faded into the background. This decision seems to have been based on a desire to emphasize the uniquely smaller and lighter sizes of Nikon's 85mm lenses, which were separated into two lines: an affordable, compact 85mm line and a faster, high-performance line that began with the Ai Nikkor 85mm F1.4S. Wakimoto, who was directly under Murakami, is said to have been greatly disappointed when the 85mm f/1.8 lens was discontinued. He couldn't believe the successor was a slower f/2!

The 85mm focal length has always been synonymous with fast, medium-telephoto lenses. With that in mind, the successor to this lens, which long reigned as the fastest medium-telephoto lens, may well be the Ai Nikkor 85mm F1.4S.

Additional information: Filters in front image sensors

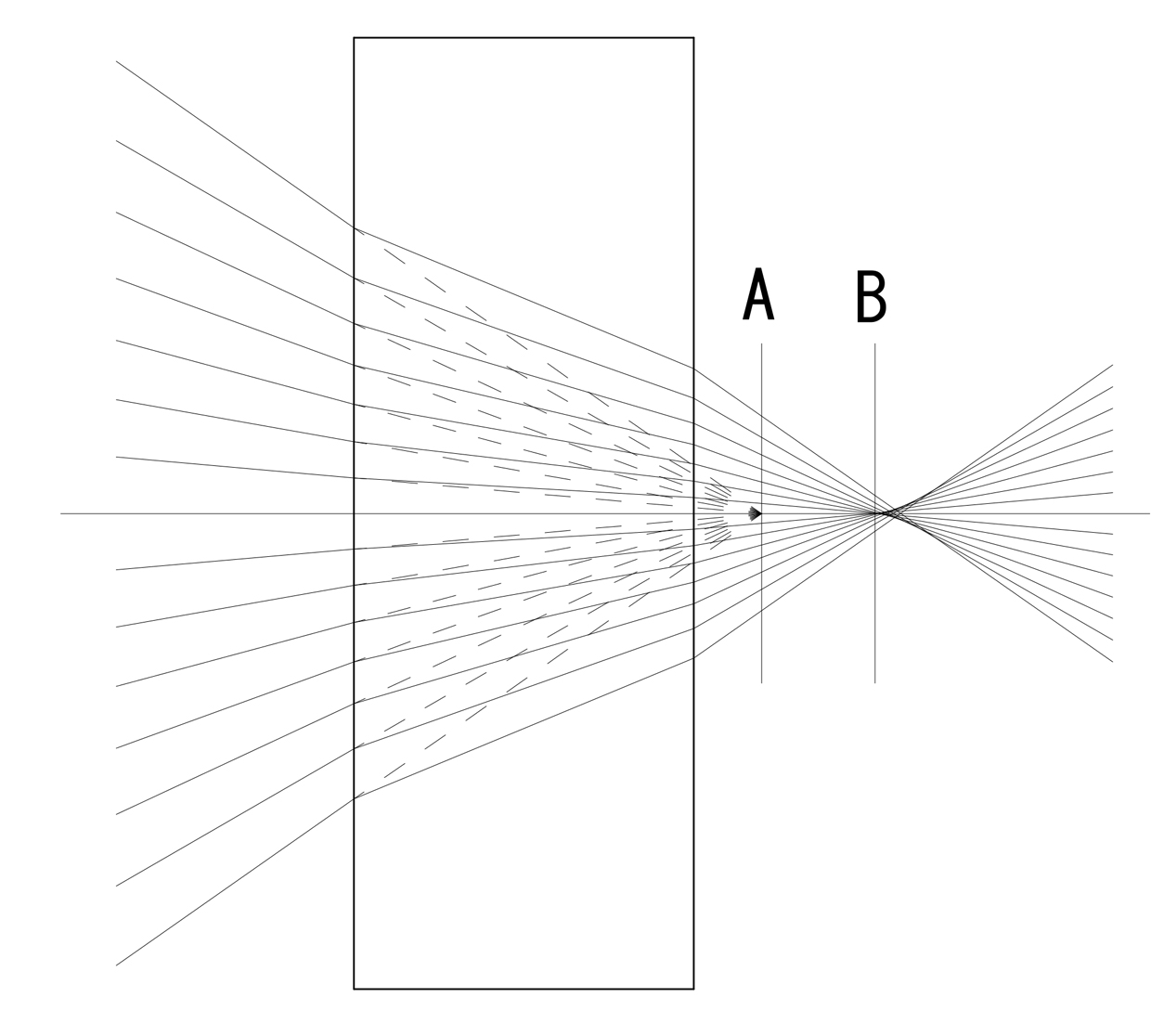

There is one thing to keep in mind when using a vintage lens designed for film cameras with a modern digital camera. That is the effect of optical low-pass filters and color filters positioned in front of the image sensor. Take a look at Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 shows how images are formed when a filter is incorporated just before the imaging position. Without a filter, light rays form the image at A with no aberration. When a filter is added, however, the imaging position shifts to B. We can also see that light rays do not converge at B, and the more angled the light rays are, the more they are concentrated to the right of B. This causes positive spherical aberration. It is one of the effects of positioning a filter in front of the image sensor. It shifts spherical aberration to a positive value (i.e., over-correction), and, as the diagram shows, the greater the angle of inclination of light rays (the lower the f-stop), the more spherical aberration occurs.

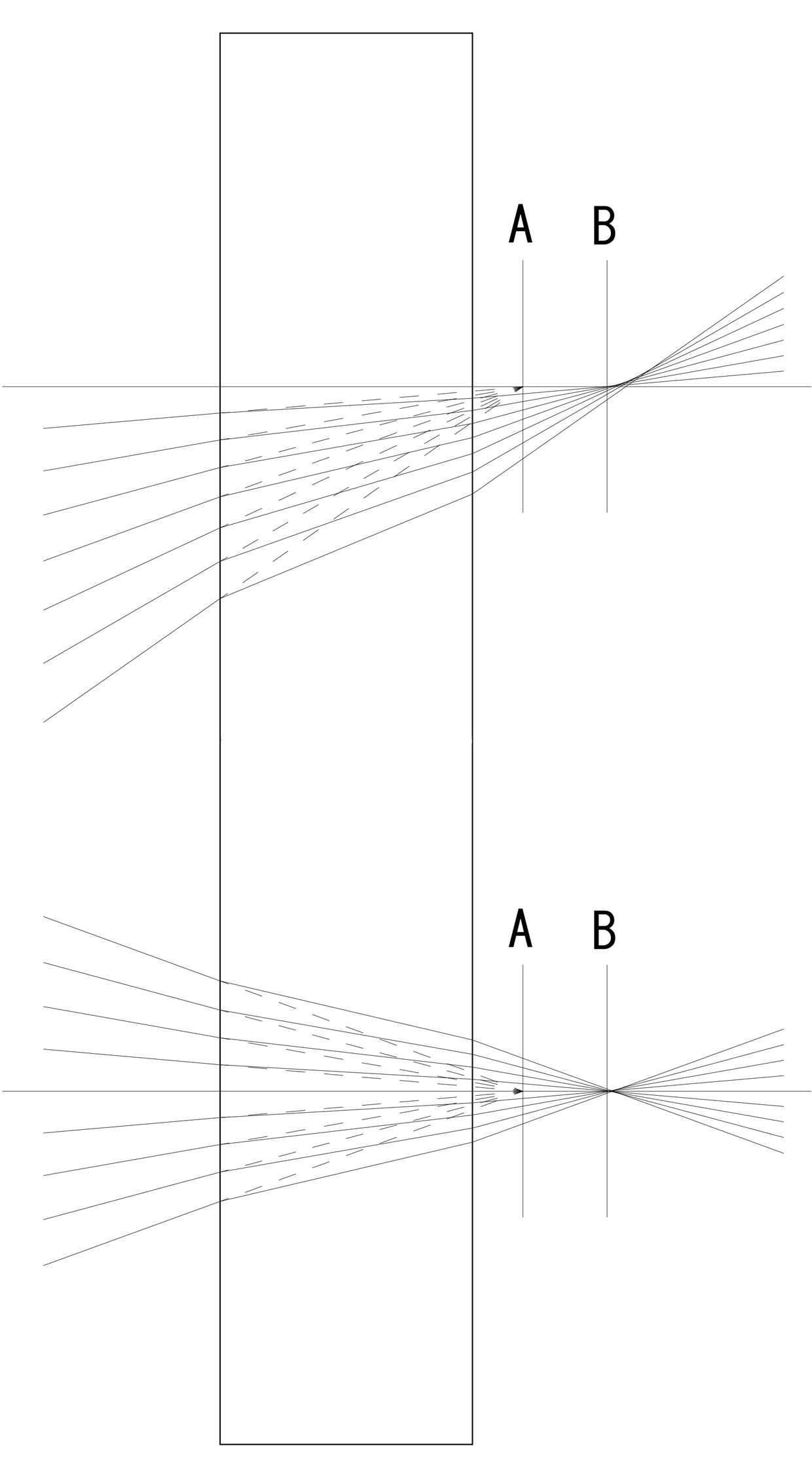

What about light rays at the edges of the frame? Because light rays are angled at the edges of the frame, imagine one side of the light rays in Fig. 2 missing. Fig. 3 illustrates the issue for easier understanding.

The optical path shown at the top of Fig. 3 illustrates image formation at the edges of the frame, while that at the bottom illustrates image formation at the center of the frame. As in Fig. 2, the image formed at the center of the frame, shown in the bottom illustration, exhibits positive spherical aberration, but the amount of this aberration is lower because the lens's f-stop is higher (slower). On the other hand, the image formed at the edges of the frame, shown in the top illustration, exhibits more aberration than at the center of the frame, and that the focus point has shifted to the right of the original imaging position B. There are two primary aberrations occurring here. One is positive curvature of field, and the other is inward coma. The filter in front of the sensor essentially causes positive spherical aberration, as well as positive curvature of field and inward coma at the edges of the frame. Further, there is more curvature of field and inward coma at the edges of the frame when lenses with small exit pupils, such as wide-angle lenses for rangefinder cameras, are used. It is helpful to keep the effects of filters incorporated before the image sensor in mind when using a vintage lens with a digital camera. I pointed out the effects of inward coma at the edges of the frame and astigmatism in the corners of the frame with Sample 3, as well as the harsh background blur caused by spherical aberration and the distorted blur caused by astigmatism in Samples 5 and 7. However, I think these defects are somewhat exacerbated by the filter(s) in front of the image sensor. Incidentally, Nikon Z-series cameras are designed so the filter(s) incorporated in front of the image sensor are as thin as possible to maximize performance when vintage lenses are used. However, please remember there is no way to completely eliminate the issues caused by these filters.

NIKKOR - The Thousand and One Nights

The history of Nikon cameras is also that of NIKKOR lenses. This serial story features fascinating tales of lens design and manufacture.