NIKKOR - The Thousand and One Nights No.39

Ai AF Zoom-Nikkor 35-70mm F2.8S

Tonight's tale is about the Ai AF Zoom-Nikkor 35-70mm f/2.8S, which was the first standard zoom lens with an aperture of f/2.8 developed by Nikon. What were the origins of this lens, and what secrets and technical innovations lay behind it? Tonight, I will unravel these secrets one by one.

by Haruo Sato

I. The difficulty with f/2.8

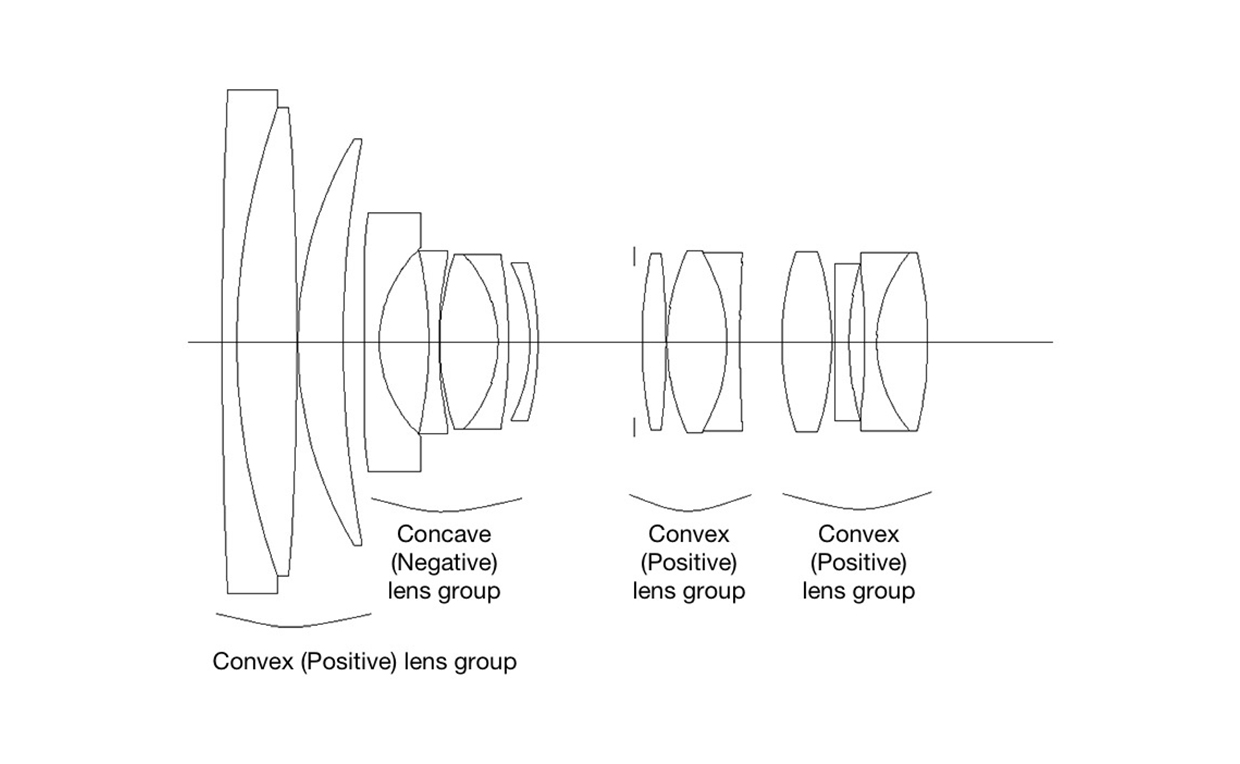

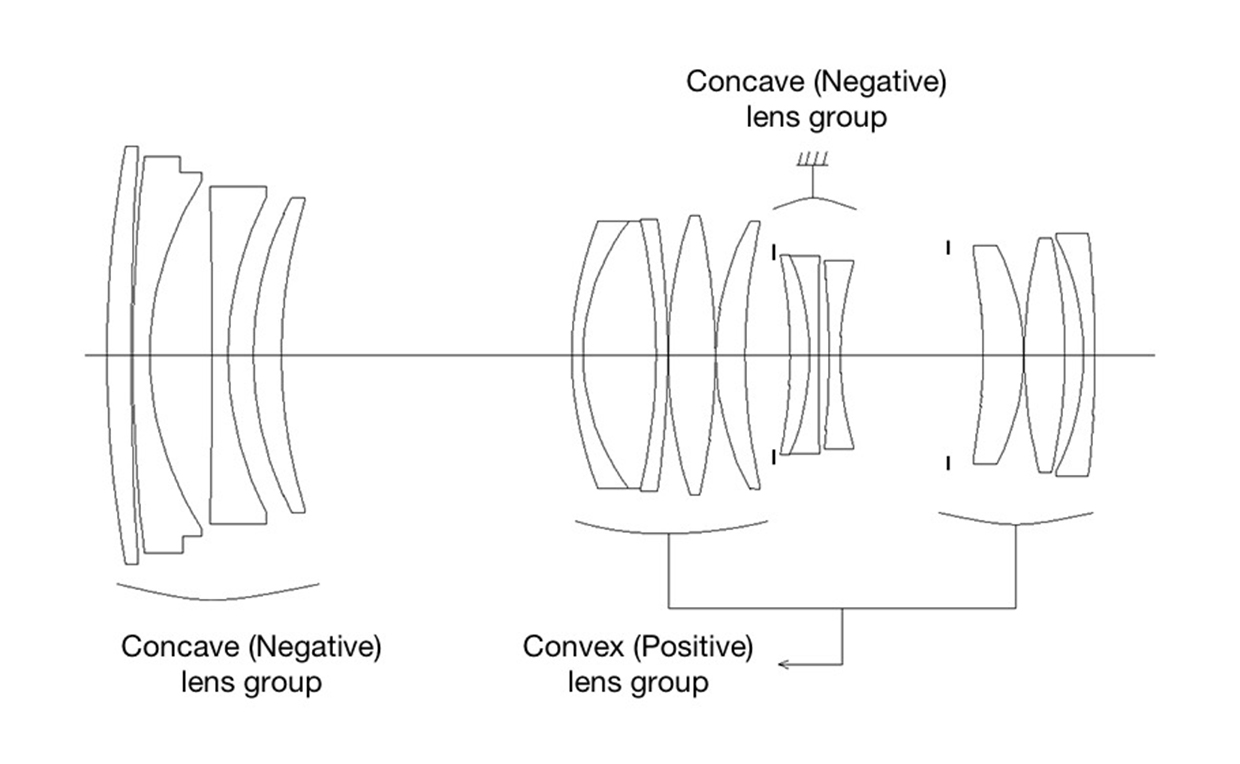

In general, zoom lenses can be broadly divided into two types: positive lead type (those with a convex lens group at the front) and negative lead type (those with a concave lens group at the front). Not only with large aperture zoom lenses, but in optical design in general, the most difficult thing is to achieve both a wide angle of view and a large aperture because both qualities cause aberation. Lens configurations must take this into account and ensure there is no aberration, especially in standard zoom lenses, which possess a relatively wide angle of view. Both lens types may be used: positive lead type (Figure 1) and negative lead type (Figure 2). The chief obstacles in aberration correction are performance and brightness at the edge of the image field at the wide-angle end, and balance between good performance in the center and at the periphery at the telephoto end. Depending on which of these is considered more important, the lens designer is forced to choose between using a negative or positive lead type.

In the latter type, the first positive lead type lens group converges the light into a thin ray, and so the concave and convex groups behind it can be small-sized. Since the aberration accompanying the large aperture generated by the rear lens group is relatively easy to correct, this configuration is effective for the telephoto end of the zoom. However, starting with a convex lens group means it is difficult to ensure brightness at the edge of the image field, and it may also mean large-sized filters are required. Conversely, a negative lead type means it is easier to achieve brightness at the edges, while it has the added advantage of being good for aberration correction for the wide-angle end of the zoom. Consequently, a configuration with a concave lens group at the front is considered better in terms of ease of design for the wide-angle end. However, because this type starts with a concave lens group, the light beam is larger, and so the convex lens group behind it must be large-sized, as well as being highly refractive power. This also creates a large amount of aberration. So, in terms of ease of design for the telephoto end, a configuration with a positive lead type is considered better. Back then, whichever of the two lens configurations the designer chose, both required extremely challenging specifications.

II. How development progressed

Now I would like to tell you about how development of the Ai AF Zoom-Nikkor 35-70mm f/2.8S progressed.

The optical design was completed in spring 1986. In September that year, prototype plans were drawn up, followed by a test model, and inspection and photography performance tests, and in winter 1987, the drawings for mass production were released. Preparations were made for the eventual launch in December 1987. The man responsible for the lens' optical design was Kiyotaka Inadome, who was in the 1st Optical Section in the Optical Designing Department at the time. Mr. Inadome was not only an excellent senior member of the team when I first joined, but someone who also supported his junior colleagues. As an optical designer he was meticulous, giving all his attention to the work, and making thorough use of simulation.

He was particularly knowledgable about the four-group zoom lens system with the negative lead type, and excelled in its design. He was indeed a man of many talents: he also developed the software for the cam calculations necessary to develop zoom lenses with IF (Internal Focusing).

Mr. Inadome was a quintessential precisionist, but also big-hearted and cheerful in the way many men from Kyushu are. He was well-known for his neat, almost geometrical handwriting, which he wrote using a small ruler with consummate ease, one perfectly straight character stroke at a time. He gave the software he developed a woman's name. I asked him about it once. Who did it refer to, I wondered. But he wouldn't tell me, and even now it remains a mystery.

III. Image characteristics and lens performance

First, as you can see from the cross-section in Figure 2, this zoom lens has a four-group configuration with a negative lead type. One feature is that it uses a fixed third concave lens group, and second and fourth convex lens groups that move together. This four-group configuration with a negative lead type is the most limited in terms of aberration correction. Why then did Mr. Inadome choose it? It is likely that he was also considering the lens barrel design and its manufacture. The lens barrel has only a single cam groove and a single lead groove. In other words, it has the same structure as an inexpensive two lens group zoom. Naturally, the simple structure lends itself to improved lens productivity. Of course, the fact that movement of each lens group is restricted is a huge encumbrance to optical design. Bearing this in mind, it is surprising to find that in actual use this lens provides excellent aberration balance. In particular, the minimal fluctuation in distortion is a real technical achievement. Furthermore, Mr. Inadome chose to use a three element concave-convex-concave cemented lens. He used this particular technique to achieve an apochromatic lens at a time when ED glass was still expensive and could not be adopted so easily.

This zoom lens did not have a single ED glass element in it, but it corrected chromatic aberration extremely well. This was also a true technical accomplishment.

Now let's examine the imaging characteristics of this lens based on design parameters, and long-range shots and photos examples. First, I'll look at design parameters in order to evaluate imaging characteristics. With the lens at the wide-angle end, both longitudinal chromatic aberration and lateral chromatic aberration are satisfactorily reduced, and so astigmatism and curvature of field are also reduced. In addition, distortion is brought down to within -3 percent. With the lens at the telephoto end, we immediately notice that astigmatism is minimal. There is curvature of field to some degree, but the minimal astigmatism allows for better depth and bokeh. Distortion is controlled well to within +2.5 percent. Slight coma aberration remains, but the degree of softness, retaining some sharpness while avoiding too hard an image, provides the perfect aberration balance for portrait use.

Nikon F100, Ai AF Zoom-Nikkor 35-70mm f/2.8S (at 35mm) Aperture f/2.8; shutter speed 1/1000 sec -0.3 EV RDP III

Nikon F100, Ai AF Zoom-Nikkor 35-70mm f/2.8S (at 50mm) Aperture f/2.8; shutter speed 1/1000 sec -0.3 EV RDP III

Nikon F100, Ai AF Zoom-Nikkor 35-70mm f/2.8S (at 70mm) Aperture f/2.8; shutter speed 1/125 sec -0.3 EV RDP III

Next, let's examine the long-range shots and photo examples. First, with the lens at the wide-angle end, contrast is good at the widest aperture, with high resolution, which gives a realistic feel. Compared to the center of the image, there is a little less resolution at the periphery, giving a rather more natural feel. Stopping down to f/4-f/5.6 improves contrast and resolution, in addition to giving greater resolution at the edges. Stopped down to f/8, the entire image becomes uniform, with good contrast and the best definition. From f/11 to f/22, sharpness gradually decreases due to the effects of diffraction. With the lens at the telephoto end, on the other hand, the widest aperture provides a natural image with good contrast and resolution, soft yet still with some sharpness. Stopping down to f/4-f/5.6, sharpness increases, with sharpness at the periphery too, giving good definition. At f/8, sharpness is further improved, giving the best definition. At f/11 to f/22, the effects of diffraction gradually begin to appear and sharpness decreases.

Example 1 was taken using the lens' widest angle at the widest aperture. As seen from the images of people, for example, the lens gives ample sharpness. In addition, as a wide-angle lens, it performs well with consistently smooth background bokeh. Example 2 was taken using an intermediate focal length (f = 50mm) with the aperture at its widest. The people and surroundings are sufficiently sharp and contrast is good.

Furthermore, the background has no quirks, the lens performing well with bokeh. Example 3 was taken with the lens at the telephoto end, again at the widest aperture. Looking closely at the lens' ability to capture individual hairs, we can see that it provides ample sharpness. Moreover, the realistic bokeh provided by this class of zoom lens is evident from the background.

More on Inadome Kiyotaka, the lens' designer

From my earlier description of Mr. Inadome, it is easy to see just how earnest he was. In this last part, though, I would like to say a little more about the more spirited side of his personality.

He was, in the tradition of the designers before him, a man who enjoyed a drink. The more he drank, the brighter and more cheerful he became. In his younger days, he was a regular late night drinker at a bar in Oimachi, so much so he was sometimes left to lock up the place after the owner had left, and occasionally he would come straight to work from there. Still, as you would expect from a man of strength, he was always as clear as day the next morning, regardless of how much he had drunk. He would just continue to work like a demon.

Let me relate a story about him, though, from the time he had quietened down a little after getting married. With both of us living in housing provided by the company, we knew each other well. In fact, we often went the same way home together, and stopped off for a drink from time to time. It was on one such day. We were on our way home after a drink as usual, and I said my goodbyes and headed off. There was a small park in front of his house, and I left him there at the entrance. But perhaps that wasn't such a good idea. The next day, when I asked him what time he had gotten home, it was clearly long after I had left him. Apparently, being slightly drunk, he had sat on a park bench and dozed off. As strong a man as he was, it seems day after day of hard work had finally caught up with him. It's a good memory I have of him even now.

NIKKOR - The Thousand and One Nights

The history of Nikon cameras is also that of NIKKOR lenses. This serial story features fascinating tales of lens design and manufacture.