NIKKOR - The Thousand and One Nights No.68

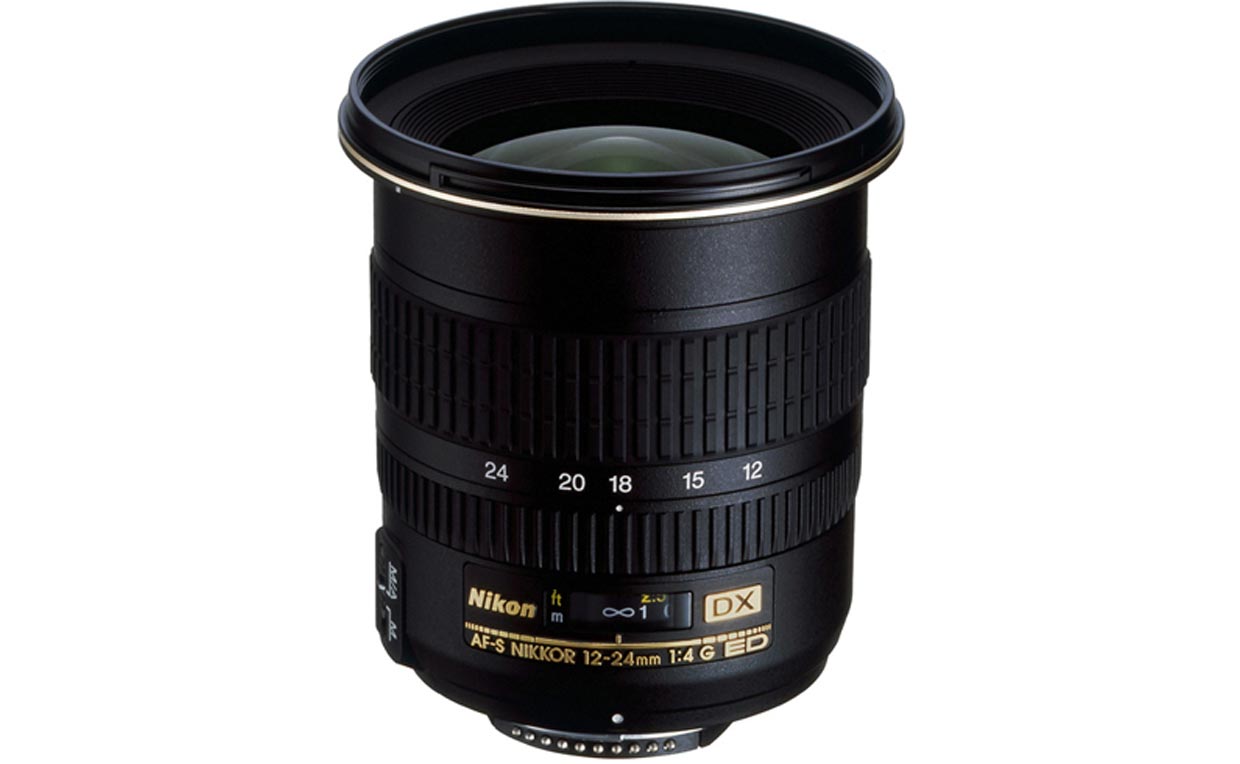

AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 12-24mm f/4G IF-ED

Tale 68 discusses the dawn of the digital SLR camera. That dawn broke on the AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 12-24mm f/4G IF-ED, the first lens for use exclusively with digital SLRs. What were the circumstances that led to the release of this lens around the same time the D2H was released in 2003?

by Kouichi Ohshita

I. The dawn of the digital SLR

The first digital SLRs sold to the public were probably introduced with Kodak's DSC series in the 1990s. Kodak achieved these cameras by equipping Nikon camera bodies with large proprietary sensors and circuit boards. As they were very expensive, and systems and environments for handling digital images were still being developed, their use was rather limited to specialized applications.

Construction of systems that could handle digital images began in the late 1990s as the popularity of Macintosh and Windows spread and digital printing technologies advanced. This helped to make digital cameras more common. In 1995, Nikon worked with Fuji Photo Film to develop the E2 and E2s digital SLR cameras, which were based on the F4. These innovative cameras differed from Kodak's DSC-series cameras in that they were equipped with a compact, 2/3-inch, 1.3-MP sensor, and achieved images with the same angle of view as those captured on 35mm film through reduction projection (reduction optics system/ROS) of the F mount NIKKOR image. Despite the high prices of these cameras with the base model E2 at ¥1,100,000, they came to be regularly used, primarily by newspapers and other press photographers.

However, while the E2 was popular for its angle of view, which was equivalent to that of the 35mm format, it did have its drawbacks. The biggest issue with the camera was that its reduction optics system (ROS) blocked a portion of the light passing through the lens. The E2 specifications state an aperture range of f/6.7-38. This means that because the amount of light passing through the lens is restricted by the ROS, the characteristics of fast (bright) lenses, such as f/1.4 lenses, cannot be achieved with the camera. In fact, the aperture had to be stopped down to f/6.7 or a larger f-number to use such lenses with the camera. This makes it very difficult to make the most of lens characteristics. In addition, the ROS was poorly matched with some lenses, and completely blocked light around the edge of the frame for severe vignetting. As a result, there were some NIKKOR lenses that simply could not be used effectively with the camera.

II. Top 01 project

Another digital camera trend arose in the second half of the 1990s. That trend was in compact digital cameras, and its best representative was the Casio QV-10. The QV-10 was one of the first consumer digital cameras to have an LCD monitor on the back, which allowed users to view images as soon as they were captured. The camera gradually grew in popularity because its images could be transferred to the personal computers that were becoming more and more common, its operation was relatively simple, and at a price of around ¥100,000, which wasn't completely out of the range of possibility for many consumers.

In June of 1996, shortly after the QV-10 was released, Nikon initiated a new development project in June of 1996. The objective of that project, carried out by a 14-member project team led by Mr. Naoki Tomino and of which I was a member, was to develop a full-scale digital camera. Predicting that the digital camera market would one day be just as large as the film camera market, Tomino had lobbied upper management for permission and resources to launch such a project. The project team, based in a small room on the third floor of the Ohi 101 Building between the north and center wings, and comprised of members knowledgeable in and experienced with various fields, including electrical engineering, mechanics, imaging, and optics, argued and discussed all aspects from their own differing positions until an outline for the ideal digital camera was achieved. For me, knowledgeable only in optical design, work with this team was very stimulating, and presented a great opportunity to expand my knowledge beyond optics.

While the primary objective of this project team, established under these circumstances, was the development of a compact digital camera that offered excellent image quality, we proceeded with considerations for digital SLR cameras in mind. Tomino, the team leader, and the entire team really wanted to revolutionize the imaging world by creating a full-scale digital SLR camera that could be sold at a price that encouraged purchase by professional and amateur photographers themselves. As our investigations and work progressed, Tomino presented upper management with the following proposal. "Let this project be like a two-stage rocket with development of a compact digital camera offering excellent image quality as the first stage, and development of a full-scale digital SLR as the second stage." His proposal was approved, and our work toward a digital SLR camera continued, and we successfully introduced the Nikon D1 digital SLR camera in 1999 just one year after completing the first stage of the project with the release of the COOLPIX 900. (Photo 2)

III. The AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 12-24mm f/4G IF-ED

The D1 was an overwhelming hit, primarily with photojournalists, because it offered the same operation, strength, and durability as the F5, with which they were already familiar, and because its price was extraordinary for a digital SLR. It was the major trend setter for digital SLRs. However, there was one problem with the D1. Because the image sensor built into the camera was smaller than 35mm film, lens angle of view was narrowed. The lens mounted on the D1 in the photo above is the (AI) AF-S Zoom-Nikkor 17-35mm f/2.8D IF-ED, which was released at about the same time as the D1. However, when this lens was used with the D1, the range of supported focal lengths shifted to 25.5-55mm, just the standard range for a normal zoom lens. While this narrowing of the angle of view has its advantages, including being convenient for telephoto photography and the excellent image quality that is achieved because only the center portion of the image circle is used, it cannot be denied that it was a disadvantage for wide-angle lenses. Therefore, from the time the D1 was released, Tomino and I hoped that, if the D1 proved to be a success, we would like to make a NIKKOR lens for use exclusively with digital SLR cameras.

That dream was put in motion in the spring of 2001 just before D1 successor models, the D1X and D1H, were released. D1 sales gradually increased, and it was a time when Nikon was planning to further cement its status in the market by releasing successor models. Planning for the next model after the D1X, the D2H, had already begun, and we planned to release a dedicated lens at the same time the D2H was to be released. The concept behind the lens was to achieve ultra-wide angles and a compact size not possible with lenses that could also be used with 35mm format cameras, as well as superior optical performance compatible with digital cameras. The person placed in charge of designing such a lens was Mr. Haruo Sato.

At the time, Sato was developing another normal zoom lens, and it wasn't the best time to work on another lens until its development is completed. Therefore, Sato came up with the design, and another designer succeeded him, creating drawings based on his design, and saw development of the lens through to the end. As this was the first lens for use exclusively with digital cameras, development began by deciding upon design objectives. While I'm sure there was some fumbling along the way, the design was completed in a surprisingly short time. Perhaps the fact that it was such a busy time for Sato with multiple designs in the works all at once led to a variety of ideas and the ability to complete the design so quickly.

IV. Lens construction

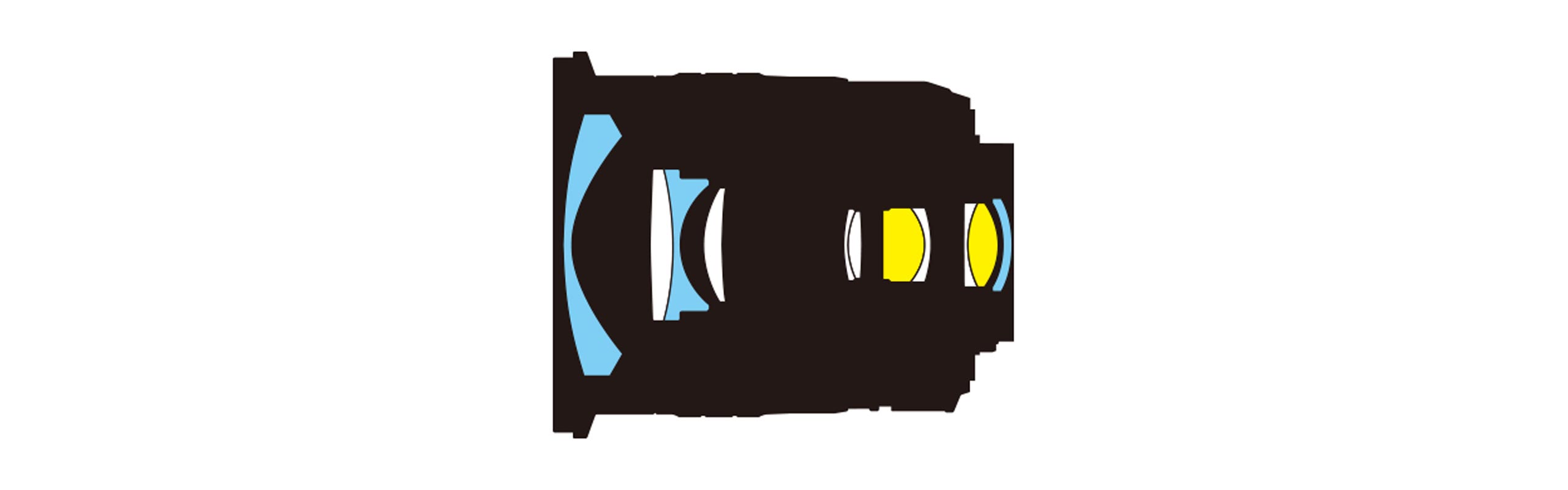

Figure 1 shows how this lens is constructed. It is a zoom lens with a two-group zoom structure for which the negative-lead structure suitable for wide-angle lenses was adopted, and with which the first group is made up of four elements and the second seven elements. Another suitable structure would have been the concave-convex-concave-convex four-group structure, and while four-group zoom lenses naturally offer greater freedom to increase performance, it is likely that Sato went with the two-group structure because of a zoom ratio of 2x, which is rather small, and a speed (brightness) of f/4, which is not extremely bright.

The characteristics of this lens lie with the structure of each lens group. Let's start with the first group. The diameter of the first lens element exceeds 50mm and both surfaces are aspherical. The aspherical element having concave surfaces on both sides is separated by a single convex element. A single aspherical surface would be sufficient if the only goal is to correct distortion. However, that does not compensate for sagittal coma flare, which would be increased by curvature of field remaining at the edges of the frame. By utilizing two aspherical elements with this lens, however, distortion, curvature of field, and coma could be suitably controlled. The field was flattened (curvature of field corrected) and sagittal coma flare reduced, all while correcting barrel distortion for pleasing results. This way of designing lenses with a negative lead zoom structure using two aspherical lens elements in the first group has since been used in designing a number of wide-angle zoom lenses.

Another characteristic of this lens lies in the structure of the second group. I want you all to remember some previous tales from NIKKOR The Thousand and One Nights. Tales 46 and 63, for example, cover NIKKOR lenses for which two-group zoom structures were adopted. I'd like you to compare the second-group structures of the lenses discussed in those tales with the one discussed here. As Sato indicated in Tale 63, the convex-convex-concave-convex Ernostar structure is likely the standard for the second group in two-group zoom structures. However, if you look at Figure 1, you won't see that structure. There is no concave lens element. The secret here is that the concave element has been separated into two elements, which were then attached to the front and back of a convex element. The Ernostar structure increases flexibility in correcting aberrations, but it comes with difficulties in that it is very sensitive to spacing between lens elements, as well as center thickness and decentering. I think that Sato chose this type that would have no strong convergence or divergence caused by a convex lens element and a concave element to eliminate these issues. Using an aspherical lens for the last element effectively compensates for aspherical and coma aberrations.

V. Lens rendering

As always, let's take a look at this lens' rendering characteristics with sample images. I used the lens with the compact, 24-MP D3300 to capture these sample images, taking it with me on walks and trips. Though the D3300 offers a pixel count that couldn't even be imagined at the time this lens was developed, because of the fact that it was developed with the expectation that pixel counts would increase, I was able to capture the images I hoped for. However, when used with a compact camera like the D3300, balance isn't as good as it would be with a somewhat larger and heavier camera like the D500 or D7500.

Sample 1 is a photo of the Milky Way captured in the summer at the 12mm maximum wide-angle position and maximum aperture. Unfortunately, light clouds at the bottom and upper right of the frame prevented sharp and clear capture of the stars. For me, the most appealing aspect of this lens is the abundance of peripheral illumination throughout the entire zoom range. With most lenses, the amount of peripheral illumination drops as the focal length decreases. With this lens, however, there is an abundance of peripheral illumination throughout the entire zoom range, and there is no noticeable lack of light volume from maximum aperture. As you can see from the mountain in the bottom left corner of this sample image, contrast was greatly enhanced to bring out the stars and Milky Way. Despite this, however, note that there is no noticeable drop in the amount of peripheral illumination. Another important feature is the lack of sagittal coma flare. Sagittal coma flare is a type of aberration that tends to become more noticeable as the angle of view increases, but it is hardly noticeable in this image. If we look very closely, we can see that stars at the edges of the frame are slightly distorted, but I think that this is quite a good starscape for having been captured by an ultra wide-angle lens at maximum aperture.

Sample 2 is a photo of a field of spider lilies captured at the maximum wide-angle position. I stopped the aperture down to f/11 for deep focus, but the foreground and farther end are still a little blurred. Even distortion has been well compensated for an ultra wide-angle zoom lens. However, some barrel distortion may be noticeable in the corners of the frame when photographing subjects at close distances at the maximum wide-angle position. Should that occur, I recommend using the camera's or Capture NX-D's auto distortion control function.

D3300 + AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 12-24mm f/4G IF-ED at 12mm, f/4.0, 71.2 s, ISO 3200 Processed with Capture NX-D

D3300 + AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 12-24mm f/4G IF-ED at 12mm, f/11, 1/60 s, ISO 400 Processed with Capture NX-D

Sample 3 is a photo of the sunset from Kōzu-shima (Kōzu Island). This photo was also captured at the 12mm maximum wide-angle position and maximum aperture. You can see the moon just past the new crescent stage at upper left in the photo. Anyone who sees a landscape as stunning as this on vacation will be glad to have brought along an ultra wide-angle lens. It is easy to get an idea of the angle of view captured with lenses with an 18mm focal length (with conversion to 35mm format) because the horizontal angle of view is approximately 90 degrees.

I zoomed in a little, and captured Sample 4 at the 14mm focal length. It is a photo of Senryo Pond, a cove on the south side of Kōzu-shima. By stopping down the aperture to f/8, I achieved consistent rendering all the way to the extreme edges of the frame.

D3300 + AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 12-24mm f/4G IF-ED at 12mm, f/4.0, 1/60 s, ISO 720 Processed with Capture NX-D

D3300 + AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 12-24mm f/4G IF-ED at 14mm, f/8, 1/250 s, ISO 100 Processed with Capture NX-D

Sample 5 is a photo of a cape in the southwest of Kōzu-shima. I zoomed in about half way to capture this photo at 17mm. The ability to shoot at the ultra wide-angle 12mm, and also to zoom in to 24mm is very convenient when traveling. I think a person could capture a great many scenes with this lens and a fast 50mm prime lens.

Sample 6 is a photo of the field of spider lilies captured at the 24mm maximum telephoto position. I stopped the aperture down to f/11 for a deep depth of field. If we compare this image to Sample 2, which was captured at the maximum wide-angle position, we see that even photos of the same subject can look and feel very different.

D3300 + AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 12-24mm f/4G IF-ED at 17mm, f/8, 1/250 s, ISO 100 Processed with Capture NX-D

D3300 + AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 12-24mm f/4G IF-ED at 24mm, f/11, 1/60 s, ISO 1100 Processed with Capture NX-D

Sample 7 is a photo of an agapanthus that I captured at a park. I zoomed in to 15mm and shot this photo at maximum aperture. If we look at the background blur (bokeh), we see consistent ring-shaped blur throughout the frame, and double-line blur along the tree trunks and branches. I suppose that you could say that these blur characteristics are a shortcoming of this lens. However, it could also be said that the consistency of the ring-shaped blur is proof of the abundance of peripheral illumination and lack of vignetting.

Sample 8 is a photo of the field of spider lilies captured at the 24mm maximum telephoto position to show blur characteristics. With this lens, double-line blur is most noticeable at mid-range focal lengths. It seems that the tendency toward double-line blur is mitigated at both 12mm and 24mm. By stopping down the aperture one stop for this image, ring-shaped blur was eliminated. This in turn makes double-line blur less noticeable. When shooting in a way that utilizes bokeh, I recommend stopping down the aperture just a little as I have done here. Some are hesitant to stop down the aperture when using a wide-angle lens so that they may make use of bokeh because doing so actually reduces the amount of bokeh. However, rings are formed as light is condensed, so stopping down the aperture just one stop shouldn't result in a noticeable reduction in the amount of bokeh.

D3300 + AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 12-24mm f/4G IF-ED at 15mm, f/4.0, 1/60 s, ISO 160 Processed with Capture NX-D

D3300 + AF-S DX Zoom-Nikkor 12-24mm f/4G IF-ED at 24mm, f/5.6, 1/60 s, ISO 200 Processed with Capture NX-D

This lens, released at about the same time as the D2H in 2003, was well received by users of the D1, D100, and D2 who were missing out on wide-angle photography, and sales of this long seller continue even today. That is probably because as the first lens for use exclusively with digital SLR cameras it was designed with such thought and care. For example, this lens was designed so that its image circle is just a little larger than that of current DX lenses. That was done because at the time this lens was developed, the designers thought that it was possible that digital SLR frame size would increase in the future. Setting such high objectives resulted in outstandingly abundant peripheral illumination and sharp and clear images at ultra-wide angles. This lens clearly offers unique characteristics just not found with others, don't you think?

NIKKOR - The Thousand and One Nights

The history of Nikon cameras is also that of NIKKOR lenses. This serial story features fascinating tales of lens design and manufacture.