NIKKOR - The Thousand and One Nights No.59

AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S

Tale 59 introduces the AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S, the fastest 100-105mm class lens of its time. This lens, the fastest in its class at the time with a maximum aperture of f/1.8, was also constructed with the fewest lens elements. This tale delves into the secrets hidden in the design of this fast lens.

by Haruo Sato

I. AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S transformations

First, let's look at the transformations the AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S underwent. The AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S was released in September, 1981. From the beginning, the AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S was a so-called AI-S lens equipped with the new auto indexing (AI) system. It is linked with the Nikon F3, a new camera released exactly one year before the AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S. It was shortly after this that the shift to AF occurred. In this time of transition, the AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S disappeared due to our inability to add AF capabilities. The AI AF DC Nikkor 105mm f/2D was released in September, 1993 as the successor to the AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S, effectively putting an end to the life of that first lens. The AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S sold for roughly twelve years. That is quite a long time for a particular product.

II. Development history and the designer

AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S optics were designed by Teru yoshi Tsunashima, introduced in Tale 13. Mr. Tsunashima stands with Ikuo Mori and Yoshiyuki Shimizu, both introduced in earlier Tales, as one of the designers who established the golden age of old Nikkor lenses. Though Japan's great lens designers are not generally known, we can trace their work through reports, development histories, notes, and patents. Mr. Tsunashima, however, was one of those people who are indifferent about small things. He did not leave a written report for each and every one of his works, making my investigation for this Tale quite difficult. Under what circumstances was the lens designed? Who came up with these specifications? What was the concept behind its design? There were no clear answers to any of these questions. However, looking back, it seems that there was a plan to renew the line of fast lenses to coincide with release of the F3. The 85mm f/1.4 and 105mm f/1.8 appear to be proof of this plan. I was completely surprised, in a good way, by the design of the 105mm f/1.8. But let's put the secrets aside for now.

Now let's take a look at the history of AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S development. Trial production drawings were issued in June of 1976. Therefore, I assume that work on the design took place somewhere between 1975 and the beginning of 1976. Mass production of the lens began in the fall of 1979, and the lens was finally released in September, 1981.

III. Lens construction and characteristics

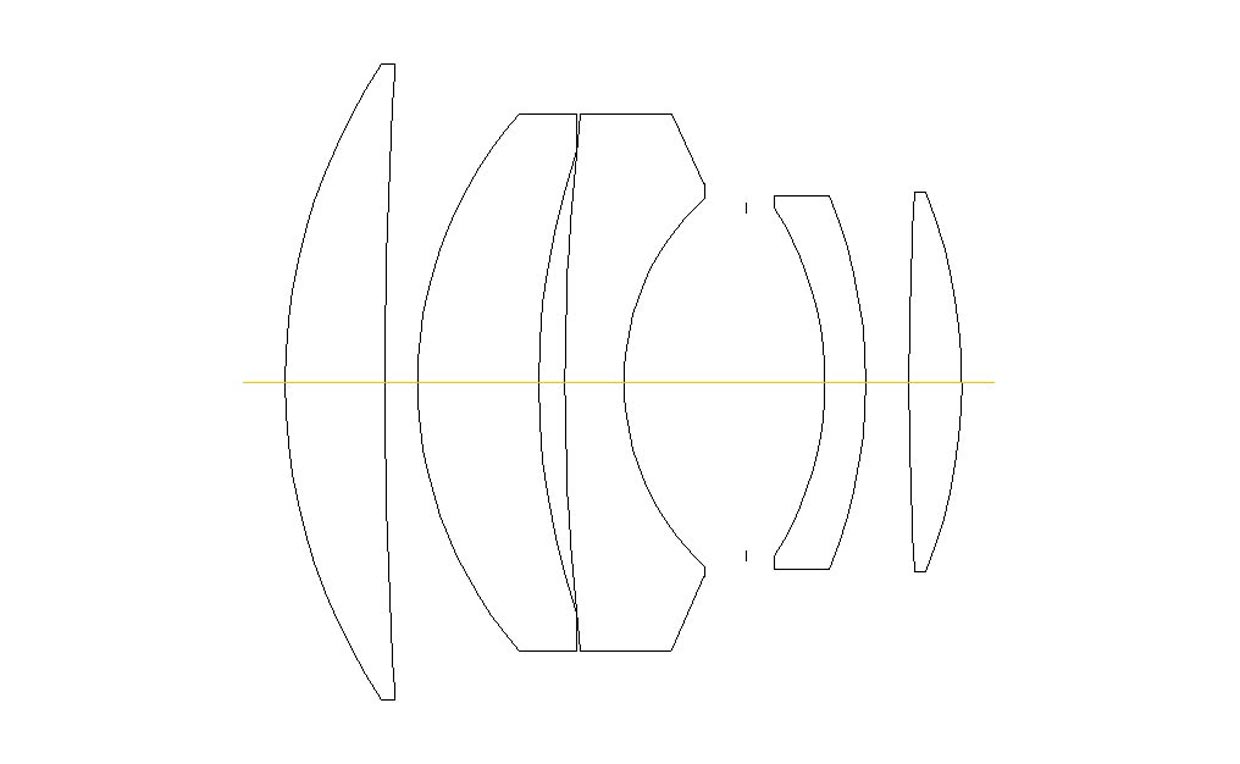

Please forgive me if the following is quite technical. First, take a look at the cross-section of the AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S (Figure 1).

I think you will immediately see that the lens utilizes typical Xenotar-type optics. The Xenotar lens released by Schneider in 1951 is said to have become the basis for Xenotar-type optics. It was explained as a sort of hybrid with the front group of Gauss type and the rear group of Topogon type. However, as Zeiss acquired a patent on a similar design prior to World War II, it is difficult to tell which came first. The Xenotar-type optics were used with many mid-level lens-shutter cameras released between 1955 and 1975. While I have also designed some lenses using this type, I much prefer the Gauss type for the balance it provides in making lenses faster and increasing the angle of view. However, the Xenotar type is superior in terms of resolution. The Xenotar type requires some skill to deal with chromatic aberration, and it can be difficult to achieve adequate contrast with optics in the f/1.4 to 2.0 class. In addition, greater precision in the thickness of the center of the concave element in the rear group was required. Therefore a Gauss doublet lens element could have resulted cheaper. Designing based on "Topogon type for the rear group" was likely correct. However, considering many design examples, it is possible that the Gauss-type doublet lens element was replaced with a single concave lens element in order to reduce costs. A lens as fast as a Gauss-type lens was achieved with a 5-element structure. This appeal leaves no doubt that the design was optimal for a mid-level lens-shutter camera lens. The AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S was also designed with Xenotar-type optics, but the 85mm f/1.4, designed at roughly the same time, had a fantastic structure that was basically a Gauss/Sonnar hybrid. Considering flexibility of design, why was the Xenotar type selected rather than the Gauss type? Why was a 5-element structure selected over a 6- or 7-element structure? These were the questions I had. This lens made me think that Mr. Tsunashima had given himself a very daunting task, and that he was challenging all possible limits. He really did achieve f/1.8 optics with a 5-element design! The AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S was truly a victory for Mr. Tsunashima.

Now let's look at the aberration characteristics of the AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S. The first thing I notice is the lack of astigmatism, and the low level of close-range aberration fluctuation from infinity to closer distances. At infinity, a full correction of spherical aberration is generally achieved. There is also little aberration fluctuation at close distances, with a slight shift in image formation position in the negative direction. What's more, there are slight differences in coma with each color, and chromatic aberration tends to be typical of the Xenotar type. However, I will say it again. With extremely little aberration at f/1.8, Mr. Tsunashima did very well to maintain the necessary degree of aberration compensation with a 5-element structure. The aberration compensation achieved with this lens is truly admirable. In addition, just as symmetrical design theory indicates, very little distortion is generated.

Now let's look at point formation. While a faint flare due to outward coma is seen around the circumference, good concentration can be confirmed regardless of whether the object is on the axis or off the axis. Typical of the Xenotar type, while resolution is fairly good, flare causes an increase in tones and soft image quality can be expected. This tendency becomes more noticeable as the shooting distance decreases, and flare characteristics tend to be similar to those of Vest Pocket Kodak's single meniscus lens. This also makes it a lens that provides aberrational balance perfect for portraits. This is the optical design that Nikon recommends and has deemed suitable for its 105mm lenses, with which it takes particular care.

Now for MTF values. Contrast is good for an f/1.8 lens at both 10 and 30 lines/mm, and is consistent throughout the entire frame. Blur increases in the background for good depth, and pleasing background blur characteristics (bokeh) can be expected. Gradual transition from the focus position enables soft rendering, and this tendency becomes more noticeable as shooting distance decreases. This mean that blur characteristics (bokeh) tend to improve at closer distances. In addition, peripheral illumination is well maintained. The rounded blur, in which the shape of so-called optical vignetting is reflected, can also be considered relatively good.

IV. Actual performance and sample images

Next let's look at results achieved with actual images. Details regarding performance at various aperture settings are noted. Evaluations are subjective, and based on individual preferences. Please keep in mind that my opinions are for reference purposes when viewing sample images and reading the evaluations.

f/1.8 (maximum aperture)

Relatively consistent resolution is exhibited from the center of the frame to the edges. Resolution is not especially noteworthy, but is definitely sufficient for portraits. Slight flare makes the entire frame look as though it's been shot through a fine veil. Color bleed is slightly noticeable. Unfortunately, axial chromatic aberration will be noticeable when used with modern systems, and there is no way around this. Colors are good.

f2.8

Stopping down the aperture to f/2.8 increases sharpness throughout the entire frame. Flare is greatly reduced and resolution is increased, but contrast is not too high as moderate contrast compression is maintained. Some color bleed remains. Results achieved at this aperture setting as well may be typical of the Xenotar type. I think that f/1.8 to f/2.8 is probably best for portraits.

f4-5.6

Flare is eliminated for even greater resolution at the edges of the frame. A satisfactory level of sharpness is achieved throughout nearly the entire frame, and color bleed is no longer an issue. Images, however, do not exhibit too much contrast. A setting of around f/5.6 is probably best for normal use.

f8-11

Consistent rendering is achieved throughout the entire frame. As contrast is greatly increased, images exhibit a little bit too much contrast. Of all aperture settings, the best image quality is achieved at f/11. An aperture setting of f/11 is best for landscape photos.

f16-22

Even more consistent rendering is achieved throughout the entire frame. At f/22, the effects of diffraction are visible and resolution drops slightly.

If sharpness is the goal, the best results would likely be achieved at an aperture setting of f/8 to f/11. For portraits, I think that I would use a setting between f/1.8 and f/2.8.

Now let's confirm these rendering characteristics with some sample photos.

So that you may judge the characteristics of this lens for yourself, compensation for lateral chromatic aberration, axial chromatic aberration, and vignetting has not been applied, and image sharpness has not been enhanced. Samples 1 through 6 are examples captured at gradually decreasing shooting distances. This allows for verification of differences in rendering according to shooting distance. Be sure to also take note of changes in blur characteristics (bokeh). Sample 6 allows us to confirm rendering with extreme close-ups.

Nikon D750/AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S

Aperture: f/1.8 (maximum aperture)

Shutter speed: 1/4000 s

ISO sensitivity: 110

Image quality: RAW

White balance: Auto

D-Lighting: Auto

Picture Control: Portrait

Captured in April 2016

Sample 1 is almost a landscape photo. The girl's face and hair exhibit sufficient sharpness to make this a pleasing image. The image is not as sharp as it might be if captured with a modern lens, but the image appears very natural. Blur characteristics are also relatively good, and there is no double-line blur. Colors are good, and chromatic aberration is hardly noticeable.

Nikon D750/AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S

Aperture: f/1.8 (maximum aperture)

Shutter speed: 1/4000 s

ISO sensitivity: 100

Image quality: RAW

White balance: Auto

D-Lighting: Auto

Picture Control: Portrait

Captured in April 2016

Nikon D750/AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S

Aperture: f/1.8 (maximum aperture)

Shutter speed: 1/4000 s

ISO sensitivity: 200

Image quality: RAW

White balance: Auto

D-Lighting: Auto

Picture Control: Portrait

Captured in April 2016

Nikon D750/AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S

Aperture: f/1.8 (maximum aperture)

Shutter speed: 1/4000 s

ISO sensitivity: 250

Image quality: RAW

White balance: Auto

D-Lighting: Auto

Picture Control: Portrait

Captured in April 2016

Samples 2, 3, and 4 were captured at distances common with portraits. The balance between sharpness and bokeh is good, and there is no breakdown with rendering.

Nikon D750/AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S

Aperture: f/1.8 (maximum aperture)

Shutter speed: 1/4000 s

ISO sensitivity: 160

Image quality: RAW

White balance: Auto

D-Lighting: Auto

Picture Control: Portrait

Captured in April 2016

Nikon D750/AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S

Aperture: f/1.8 (maximum aperture)

Shutter speed: 1/4000 s

ISO sensitivity: 100

Image quality: RAW

White balance: Auto

D-Lighting: Auto

Picture Control: Vivid

Captured in April 2016

Sample 5 was captured at nearly the closest possible distance. Even at this distance, the good level of sharpness needed is maintained. Sample 6 was captured at the closest possible distance. Even in the very small portion of the frame that is in focus, you can see that sharpness drops slightly.

Overall, it is clear that despite being a fast lens, the AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S offers a degree of sharpness more than sufficient for practical use, as well as pleasing bokeh. Resolution is relatively good, so sharpness can be controlled by making full use of image processing. It is difficult to create a more three-dimensional appearance, or to correct double-line blur with image processing. However, contrast can be adjusted freely. In addition, a slight amount of sharpening does not negatively affect the smooth bokeh (because objects are already blurred). In short, the balance in image quality offered by this lens is well suited even to today's digital age.

V. 85mm? 105mm?

When asked what the best focal length is for portraits, some will answer 85mm and others 105mm (100mm). I refer to the two groups as the 85mm segment and the 105mm segment. To be honest, I've always been part of the 105mm segment. The 105mm f/2.5 has been one of my favorite lenses since I was in middle school. Naturally, one is really no better than the other. It is simply a matter of preference and taste. Why are there two segments, though? I considered this question myself. When those from the 85mm segment were asked which shorter and longer focal length lenses they used, it became clear that 35mm lenses were used more often than 50mm lenses. The most common line of lenses used is the 35mm/85mm/135mm line. It turns out that, relatively speaking, wide angles are preferred by users from this segment. On the other hand, those from the 105mm segment most frequently use the 50mm (58mm)/105mm/180mm (200mm) line of lenses. I myself have long used a 58mm lens for portraits. As the difference in angle of view between the 58mm and 85mm focal lengths is surprisingly small, I hesitate to change lenses. While not everyone may agree with me, I'm sure there are many who share my point of view. I'm quite certain that the AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S was a lens in great demand by those of the 105mm segment.

Nikon has recently released the new AF-S NIKKOR 105mm f/1.4E ED, a 105mm lens that inherits the concept and ideas behind the traditional AI Nikkor 105mm f/1.8S while supporting the latest technical advances. This lens was developed with the same design concept as the AF-S NIKKOR 58mm f/1.4G in mind. That is, "improved three-dimensional rendering characteristics". While images captured with the AF-S NIKKOR 105mm f/1.4E ED are just a little sharper than those captured with the 58mm f/1.4G, overall image characteristics are the same. I sincerely hope that you will try this latest offering from Nikon.

So, are you part of the 85mm segment, or the 105mm segment?

NIKKOR - The Thousand and One Nights

High technology that supports the deep trust of the Nikon brand. It is the result of active technology and research and development that has been continuously continued since its establishment in 1917.